Rose-painting

Rose-painting, rosemaling, rosemåling or rosmålning is a Scandinavian decorative folk painting that flourished from the 1700s to the mid-1800s, particularly in Norway. In Sweden, rose-painting began to be called dalmålning, c. 1901, for the region Dalecarlia where it had been most popular, and kurbits, in the 1920s, for a characteristic trait, but in Norway the old name still predominates beside terms for local variants. Rose-painting was used to decorate church walls and ceilings. It then spread to wooden items commonly used in daily life, such as ale bowls, stools, chairs, cupboards, boxes, and trunks. Using stylized ornamentation made up of fantasy flowers, scrollwork, fine line work, flowing patterns and sometimes geometric elements give rose-painting its unique feel. Some paintings may include landscapes and architectural elements. Rose-painting also utilizes other decorative painting techniques such as glazing, spattering, marbleizing, manipulating the paint with the fingers or other objects. Regional styles of rose-painting developed, and some varied only slightly from others, while others may be noticeably distinct.

Etymology and terminology

The term derives from ros, applied decoration or embellishment, decorative, decorated [rosut, rosute, rosete, rosa] and å male, to paint. The first element can also be interpreted as a reference to the rose flower, but the floral elements are often so stylized that no specific flower is identifiable, and are absent in some designs.[1]

In Sweden the style was traditionally called rosmålning,[2] with cupboard decorations said to be utkrusat i rosmålning or krusmålning. In the 20th century the terms dalamålning or dalmålning and kurbitsmålning came into common use.[3] Dalamålning refers to Dalarna, with which the style is particularly associated;[4] the term appeared around 1901.[5] Kurbits originally derived from the Latin Cucurbita, and refers to a long-bodied gourd. The poet Erik Axel Karlfeldt, who wrote about the painted wall hangings of Dalarna,[6] popularized the term in the 1920s, particularly in his 1927 poem "Kurbitsmålning".[7]

History in Norway

In Norway, rose-painting, or rosemaling, originated in the 1700s in the lowland and rural areas of eastern Norway, particularly the in the Hallingdal and Telemark regions, but also the Valdres, Numedal, Setesdal, Gudbrandsdalen, and in other valleys in Vest-Agder, Hordaland, Sogn og Fjordane, and Rogaland.[8] Rural artists, influenced by Baroque and Rococo styles of the upper classes, encountered through craftsman's guilds, applied the new ideas to their traditional art styles.[9][10] Rose-painting was originally used to decorate the walls and ceilings of churches and homes of wealthy families.[11] As the 18th century progressed, more and more individuals became artists, allowing for more development of the fledgling art form.[12] Some historians suggest that this was possible due to an increased desire for art, as the style of rural Norwegian homes had changed, with the introduction of chimneys, which vent smoke out of the house, meaning walls could now be painted without becoming smoke damaged.[12] While at first only the rich were able to afford rose-painting decorations, by the mid-18th century, more and more people were able to afford rose-painting in their own homes.[10]

Free from the restrictions of guilds, rural artists were free to develop their own styles of this folk art, influenced by various trade routes through their regions, resulting in different regional styles of rose-painting.[13][14] The three main regional styles are Telemark, Hallingdal and Rogaland, named after the regions in which each originated.[15][16] Early painters traveled, spreading their style where they went, which accounts for some of the commonalities between regions.[14] Not only did artist paint walls and doorways, they often painted home goods, such as beds, food containers, and trunks.[17] As rose-painting became more popular, artists began to initial their work, allowing historians to study how the craft was taught, and how prolific different artists were.[18] By the 1850s, the popularity of rose-painting began to decline, as industrialization meant that factory-made products became affordable, and immigration meant that people were leaving Norway in large numbers.[13] Rose-painting was saved however by a growing middle-class that supported a folk art movement in Norway, ensuring the survival of rose-painting for future generations.[17]

Rosemaling is, in a sense, the two-dimensional counterpart of acanthus carving, since it is clear that the C and S curves in rosemaling take their inspiration from the acanthus carvings of Baroque and Rococo art and the acanthus carvings in rural churches (for example the altar reredoses and pulpits) and homes (for example cupboards) were painted in the same bright colors as used in rosemaling. While in the cities these acanthus carvings were generally gilded, the rural artisans did not have ready access to gold leaf as their urban counterparts and so painted their carvings in the bright colors whose popularity in rural communities is seen also in the traditional Norwegian rural dress, the bunad. Like rosemaling, acanthus carving has had a cultural revival in recent times as both a means of interior design (for example, on furniture, picture frames, and door and window frames) and as a personal hobby, although most modern acanthus carving is left unpainted and unvarnished.

Rose-painting is closely associated with Norway, and as such has been used at various points throughout Norwegian history to represent Norwegian pride and nationhood. During the Nazi occupation of Norway (1940–1945), at a time when the public display of the Norwegian flag or the State Coat of Arms could bring imprisonment or even death, the Stavanger firm of Åsmund S. Lærdal published a series of anti-Nazi Christmas cards in December, 1941. The cards wished readers a "god norsk jul" or Merry Norwegian Christmas, and featured symbols of Norway, such as trolls, the Norwegian flag, and a rose-painted trunk.[19] The rose-painted design on the trunk hid a stylized H7, which was used by Norwegians to show support for their exiled king, Haakon VII. The Nazis, upon discovering the hidden message in the cards, confiscated the entire series from the printer and shops, and ordered postmasters to confiscate any cards from the series they encountered in the mail.[19]

Today, rose-painting's popularity in Norway has continued. Institutions such as folkehögskolen, or folk high schools in Norway teach students traditional crafts, such as rose-painting.[20] This is further supported by other institutions, such as the Norske Kunsthåndverkere, or Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts, which was established in 1975 by the Norwegian Ministry of Culture. This institution helps support dues-paying members, granting them the opportunity to hone their art.[20] These various methods of support and education in traditional crafts have ensured their continuation into the 21st century.

Rosemaled items are also of great interest to tourists, who can buy items from shops and museums throughout Norway. Cheaper rosemaled objects are mass-produced with the use of stencils, while more expensive hand-painted items are individual works of art, and can therefore be quite expensive.[21] Rosemaled objects raange from bowls, vases, to chests, jewelery boxes, and larger pieces of furniture.[21] It is not only tourists that are interested in rosemaled items however, as rose-painting remains a national symbol of Norway, and is still popular.[20]

Modern rose-painted designs hold many similarities to historic rose-painting in Norway. Some artists still follow traditional design when rose-painting, while others have adapted the traditional styles to create something new. Since rosemaling in Norwegian simply means "decorative painting," there are often many other designs included beyond the traditional floral depictions. Designs can involve agricultural landscapes, scenes from historical events, life in rural areas, scenes from children's stories, fairytales, and more. More and more styles have emerged beyond the famous Telemark, Hallingdal, and Rogaland styles.[21] Many of these styles were brought to America by Norwegian immigrants, as described in the history in America section below. Rose-painting is considered by many Norwegians as a way to keep a shared identity and culture among their entire nation.

While shops and museums will most likely contain rose-paintings from all areas of Norway, rose-painting is currently most prominent in the southern parts of Norway. In specific, the regions Telemark and Hallingdal are booming with this folk art. Regardless of being most popular in the southern region of Norway, however, the rose-paintings still do vary quite decently from city to city. This is why the styles have always been regionalized and regionally named. For instance, Telemark tends to produce rose-painting with a more exaggerated and ornate style. It follows an 18th-century French influence and inspiration. Hallingdal, on the other hand, produces its own style of work. These artists, unlike many others, tend to prefer selling their work privately rather than within shops.[22]

History in Sweden

In Sweden, it is a style of painting featuring light brush strokes and depictions of gourds, leaves, and flowers, used especially in the decoration of furniture and wall hangings, and was adopted by both artists and artisans in rural Sweden, reaching its greatest popularity in the latter half of the 18th century.[3][23] While rose painting was popular among the entire nation, lots of times the houses of more wealthy individuals had more rose paintings as they were able to afford more decorations. In addition, the major popularity of rose painting in Sweden occurred before the industrialization period. After industrialization, it did not disappear due to the fact that the art created during this period was recognized as a major part of Sweden's folk culture and heritage.[24]

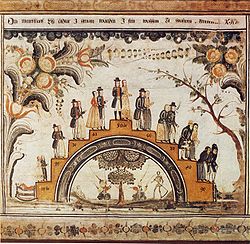

The tradition of painted wall hangings in this style was fully developed around 1820. The paintings were done by itinerant painters, most from Dalarna, whose signatures can be found in many localities.[25] The artists learned it as a trade or handicraft from one another, and copied each other's works; some pieces have been found copied more than 140 times. Artists also used stamps to create small details in patterns. Those from the Rättvik school of art were more likely to add spontaneous leaves and flowers, breaking up the symmetry of their pieces. Many of the paintings also included a zig-zag pattern at the bottom of the painting, called ullvibården after the village of Ullvi. Scenes were based on Bible illustrations, with people and buildings rendered in the then current styles.[26] The gourds reference a Biblical legend about Jonah sitting beneath a gourd;[2][27] the gourd symbolizes vegetal fertility. The most common themes of kurbit art are the wedding at Cana, Jonah preaching, the entry of the Queen of Sheba, the three wise men, Jesus riding into Jerusalem, the story of Joseph, the ten virgins, the crowning of Salomon, and the vineyard.

The style is widely found in the regions of Dalarna and southern Norrland, and today kurbits can refer to the painting of furniture, tapestry, Dala horses, or Swedish folk painting as a general concept. On the Dala horse, a gourd is used to indicate the saddle.[27]

Kurbits artists include Winter Carl Hansson of Yttermo and Back Olof Andersson, who painted in 1790–1810.

The kurbits style was used in the candidate city logo of the Stockholm-Åre bid for the 2026 Winter Olympics, forming the year "2026".

History in America

Norwegian immigrants brought the art of rosemaling to the United States.[28] Immigration from Norway to America first began in the 1830s. It is not surprising this specific form of folk art was brought to America by Norwegian immigrants since it was not just used for decoration and aesthetic purposes in Norway, but also for self-definition. Rosemaling was a way for Norwegian-Americans to keep a hold of some of their heritage.[24] During this time period of immigration, immigrants did just that, and they maintained a strong ethnic identity both privately and publicly. They might have specific traditions within their homes, participate in ethnic festivals, and more. Rose paintings were often displayed in these festivals.[29] In addition, lots of immigrants traveling from Norway to the Midwest regions of America would actually create rose paintings in churches on their travel to make some money. These rose paintings done by travelers helped expand the variation of styles among rose paintings.[30]

The art form experienced a revival in the 20th century as Norwegian-Americans became interested in the rosemaling-decorated possessions of their ancestors.[31] Rosemaling artists whose work was recognized by newspapers and magazines allowed the art form to be further recognized and grow.[30] One prominent rosemaling artist Per Lysne, who was born in Norway and emigrated to Wisconsin, was trained in the craft. Lysne is often considered the father of rosemaling in the U.S.[32] As the revival continued on, it reached its peak in the 1960s to the 1980s. In the late 1960s, Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum in Decorah, Iowa began to exhibit rosemaling. The museum then began bringing Norwegian rosemalers to the U.S. to hold classes.[33] The style's popularity boomed in the U.S., even among non-Norwegians. Other classes can be found throughout the country, especially in areas where Norwegians settled.[34]

The Swedish settlement of Lindsborg, Kansas is known for Dala horses among other celebrations of its heritage.[35]

Currently, rose painting is still most common in the Upper Midwest. This is due to the fact that when Norwegians most heavily migrated between the 1840s and 1910s, they ended up living in the Upper Midwest. In addition, the Norwegian-American Museum is still offering workshops on rosemaling. Besides workshops, rosemaling can also be taught through books, classes, and heritage centers.[30] This is very valuable as it offers more ways for Norwegian-Americans (and other Americans) to pass on rosemaling skills and traditions to future generations.[36]

To this day, there is now a decent amount of Norwegian-Americans from the Upper Midwest who have taken on rose painting, causing some of their styles to be considered "Americanized." Rather than being seen as a piece of Norwegian heritage, it is seen as a piece of Upper Midwest communities.[30] Some rosemaling styles have been "Americanized" beginning between 1930 and 1960. Compared to traditional styles, often they included brighter colors, special ornamental details, and more. Dane County, Wisconsin, which developed a style known as American Rogaland and American Telemark style found in Milan, Minnesota.[37]

Styles

There are many different styles of rosemaling. Typically, each style is named after the region it is most commonly used in.[30] To begin, the first style that has gained major popularity is the Telemark style. This style is extremely popular in Norway, and it is very impromptu. It normally involves a root center that has floral depictions or branches swirling out from it. Within the Telemark style, there are also two other styles. The transparent Telemark, which has light enough brush strokes to almost be seen through, and the American Telemark, which is a combination of both the regular Telemark style and the transparent Telemark style. Another popular style in Norway is Hallingdal. Hallingdal is different from Telemark in that the paint is often less translucent and more bold in color. In addition, it has much more symmetry and pattern to it. In addition to these, the Rogaland style also has some popularity. This style consists of more floral images than lines or scrolls. It often will have a darker background with a central flower surrounded by leaves and other decorations. While those three forms are popular, there still are other forms as well. For instance, another style is the Valdres style. The Valdres style is one that has some of the most realistic looking floral designs.[37]

Gallery

-

Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo

-

Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo

-

Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo

-

Norsk Folkemuseum,Oslo

-

Rose painting in Uvdal Stave Church, Buskerud, Norway

-

A wardrobe from Tolvmansgården, birthplace of Erik Axel Karlfeldt

-

Phone booth in Tällberg, Dalarna, Sweden

-

1799 wall painting, Bingsjö, Dalarna, Sweden

References

- ^ "What is Rosemaling?". 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b Mats Hellspong and Barbro Klein, "Folk Art and Folklife Studies in Sweden", in: Barbro Klein and Mats Widbom, eds., Swedish Folk Art: All Tradition Is Change, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN 978-0-8109-3849-6, p. 34.

- ^ a b "Dala painting". American Swedish Institute (Search results). Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ "Dala FolkArt – Folk Art and Folklore from Sweden". Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "dalmålning". Svensk ordbok (in Swedish). Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Mats Hellspong, "Folk Art from a Regional Perspective: Some Local Masters", in: Barbro Klein and Mats Widbom, eds., Swedish Folk Art: All Tradition Is Change, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN 978-0-8109-3849-6, p. 87.

- ^ Mjöberg, Jöran (1945). Det folkliga och det förgångna i Karlfeldts lyrik (in Swedish). Natur och kultur. p. 125.

- ^ Olson, Daron W. (2006). Building a Greater Norway: Emigration and the Creation of National Identities in America and Norway, 1860–1945 (Thesis). Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. ProQuest 304974864.

- ^ Kummerer, Wendy (29 February 2000). "Folk Art of 'Rosemaling' shows of Norwegian Use of Colors, Creativity". The Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 418995367.

- ^ a b Rider, Peter (1994). Studies in history and museums. University of Ottawa Press. doi:10.1353/book65667. ISBN 978-1-77282-409-4.

- ^ "What is Rosemaling?". 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b Burke, Peter (1977). "Popular Culture in Norway and Sweden". History Workshop. 3 (3): 143–147. doi:10.1093/hwj/3.1.143. JSTOR 4288103.

- ^ a b Kummerer, Wendy (29 February 2000). "Folk Art of 'Rosemaling' shows of Norwegian Use of Colors, Creativity". The Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 418995367.

- ^ a b "What is Rosemaling?". 10 May 2018.

- ^ Schreurs, Olav. "Velkommen til rosemalingens hjemmeside". Universitetet i Oslo (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ Helen Elizabeth Blanck, Rosemaling: The Beautiful Norwegian Art, Saint Paul, Minnesota: Woodland Park Fine Arts, 1975, ISBN 978-1-932043-08-2.

- ^ a b Rider, Peter (1994). Studies in history and museums. University of Ottawa Press. doi:10.1353/book65667. ISBN 978-1-77282-409-4.

- ^ Burke, Peter (1977). "Popular Culture in Norway and Sweden". History Workshop. 3 (3): 143–147. doi:10.1093/hwj/3.1.143. JSTOR 4288103.

- ^ a b Stokker, Kathleen (Summer 1996). "Hurry Home, Haakon: The Impact of Anti-Nazi Humor on the Image of the Norwegian Monarch". The Journal of American Folklore. 109 (433): 293–294. doi:10.2307/541532. JSTOR 541532.

- ^ a b c Litsheim, Mary Etta (2010). The Evolution of Scandinavian Folk Art Education within the Contemporary Context (Thesis). University of Minnesota.

- ^ a b c Merin, Jennifer (29 March 1992). "Scandinavian designs Get on board with tips to find genuine Norwegian rose-painted products". Chicago Tribune. p. 12. ProQuest 283342616.

- ^ Merin, Jennifer (29 March 1992). "Scandinavian designs Get on board with tips to find genuine Norwegian rose-painted products". Chicago Tribune. p. 12. ProQuest 283342616.

- ^ "Swedish kurbits paintings". 20 February 2012.

- ^ a b Burke, Peter (1977). "Popular Culture in Norway and Sweden". History Workshop. 3 (3): 143–147. doi:10.1093/hwj/3.1.143. JSTOR 4288103.

- ^ Hellspong, p. 88.

- ^ Hellspong and Klein, p. 33.

- ^ a b "About Dala Horses". Hemslojd Swedish Gifts. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Nils Ellingsgard, Norwegian Rose Painting in America: What the Immigrants Brought, Oslo: Aschehoug AS, 1993, ISBN 978-82-00-21861-6.

- ^ Christianson, J. R. (2000). "Review of The Promise Fulfilled: A Portrait of Norwegian Americans Today". Journal of American Ethnic History. 20 (1): 112–114. doi:10.2307/27502666. JSTOR 27502666. S2CID 254491885.

- ^ a b c d e "Revived and Redesigned: Rosemaling in the Upper Midwest." Nordic Folklife, folklife.wisc.edu/projects/revived-and-redesigned-rosemaling-in-the-upper-midwest/.

- ^ Philip Martin, Rosemaling in the Upper Midwest: A Story of Region & Revival, Mount Horeb, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Folk Museum, 1989 ISBN 978-0-9624369-0-1.

- ^ "Per Lysne". Archived from the original on 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Vesterheim Home". Vesterheim Norwegian-American. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ "Rosemaling". Rosemaling Classes. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Schnyder, Melinda (30 June 2019). "Free food, fireworks and wild Dala horses commemorate Lindsborg's 150th anniversary". Wichita Eagle.

- ^ "Folk, fine art on exhibit". Chicago Defender. 18 August 1973. p. 13. ProQuest 493919265.

- ^ a b "A Style of Their Own: Upper Midwestern Rosemalers". Nordic Folklife. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

Further reading

- Nils Georg Brekke, "Dalmålningarna som rosmålning: Ikonologiske studier i eit jamførande perspektiv", in: Nils-Arvid Bringéus and Margareta Tellenbach, eds., Dalmålningar i jämförande perspektiv: föreläsningar vid bildsymposiet i Falun och Leksand den 13–16 september 1992, Falun: Dalarnas Museum, 1995 (in Nynorsk)

- Diane Edwards, Design Basics for Telemark Rosemaling, self-published, Alamosa, Colorado, 1994, ISBN 978-1-4637-3475-6

- Sybil Edwards, Decorative Folk Art: Exciting Techniques to Transform Everyday Objects, London: David & Charles, 1994, ISBN 978-0-7153-0784-7

- Margaret M. Miller and Sigmund Aarseth, Norwegian Rosemaling: Decorative Painting on Wood, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1974, ISBN 978-0-684-16743-5

- Gayle M. Oram, Rosemaling Styles and Study, Volume 2, Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum, 2001

- Harriet Romnes, Rosemaling: An Inspired Norwegian Folk Art, self-published, Madison, Wisconsin, 1951, repr. 1970

External links

![]() Media related to Rosemaling at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rosemaling at Wikimedia Commons